Darren Milligan is more than an educator. He’s an architect of a revolution in the global learning community. Here’ s his take on the Smithsonian’ s digital leadership.

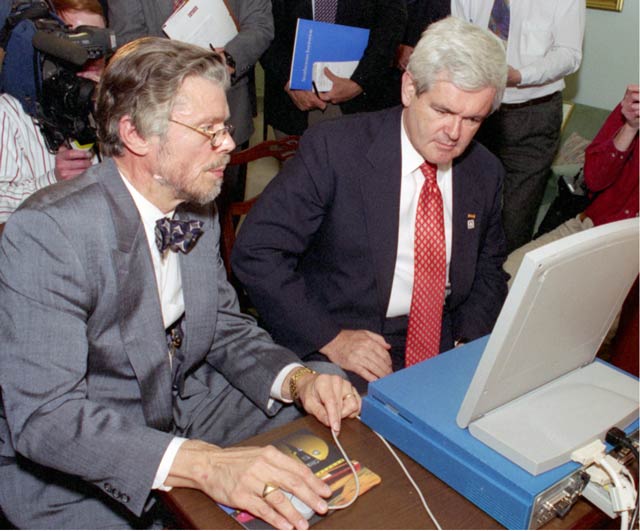

The first day the Smithsonian went online, flipping the switch was so novel and momentous that it took place at a ceremony in the office of the Speaker of the House. In the 22 years since, that first website has morphed into hundreds and spawned mobile apps and countless social-media platforms. Today, far more people interact with the Smithsonian online than by visiting in person.

This astonishes me.

In the decade I have worked here, the digital Smithsonian and its potential to inspire and facilitate learning everywhere have become so important I take them for granted. The internet has become the foundation, the very infrastructure, that enables and connects the many threads of our lives.

The ways in which we reach out and educate; our scientific, historical and cultural research and the museum experience are supercharged by this digital infrastructure.

We—well, the more than 3 billion of us currently online—have the opportunity to access and connect, to share our own perspectives, our experiences and play a greater role in bringing about the increase and diffusion of knowledge through the Smithsonian.

We are in the middle of a remarkable moment, and this has meant amazing things in 2016.

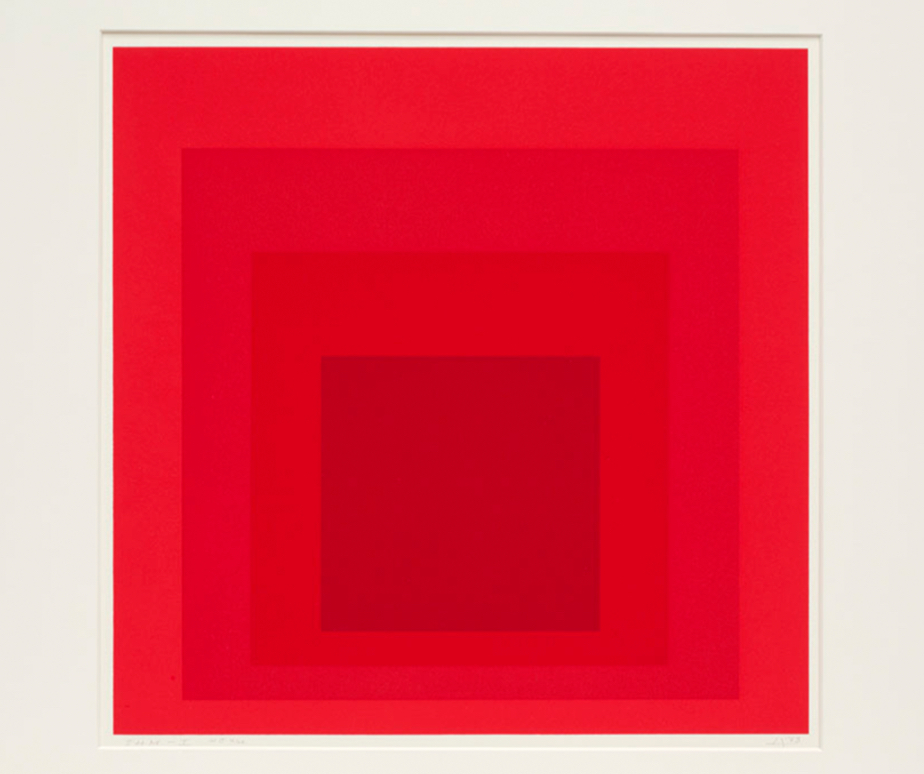

For me, I launched a long-held dream, the Smithsonian Learning Lab. The premise is simple. Lab users select Smithsonian digital resources, such as the National Portrait Gallery’ s painting of Martha Graham dancing or a video of a National Museum of Natural History scientist explaining how she started her career, to build their own personal “ collections.” They add educational features as needed online. Their choices of what to collect, powered by the lab, make magic.

Suddenly, a series of paintings teaches the principles of geometry, a sequence of videos are combined to explain media criticism or personal images are uploaded to complement our national collection.

The outcomes have been as varied and creative as our users, who are enthusiasts, teachers and students. In less than a year, makers have created almost 10, 000 personalized collections, which can be copied and modified even more, as one user builds upon another’ s work.

“ THE OUTCOMES HAVE BEEN AS VARIED AND CREATIVE AS OUR USERS.”

I’ve been at the Smithsonian a long time, as have some of my colleagues. We marvel at how our audiences are making the digital Smithsonian their own in ways we never thought of or could imagine. They are not replacing our curators and experts, but rather expanding upon our work.

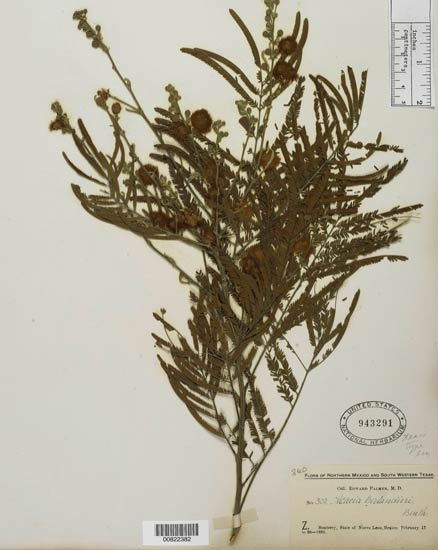

Using cutting-edge machine learning, botanists at the National Museum of Natural History along with digitization teams and data scientists from the Office of the Chief Information Officer are “teaching” computers how to identify plant species, with greater accuracy than humans.

Thousands of digital volunteers from across the world are turning handwritten manuscripts into narratives through the Transcription Center, a platform launched in 2014. No longer just unidentified pictures, these transcriptions make our “digitized” objects searchable and usable by scholars, teachers and students.

In 2016 alone, 76, 546 pages were transcribed, including 1, 000 pages from the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, the records of the Freedmen’s Bureau, enabling a deeper and richer understanding of the post–Civil War transition of enslaved people to freedom.

“ This adaptation of our digital information will continue as our audiences grow and technology changes.”

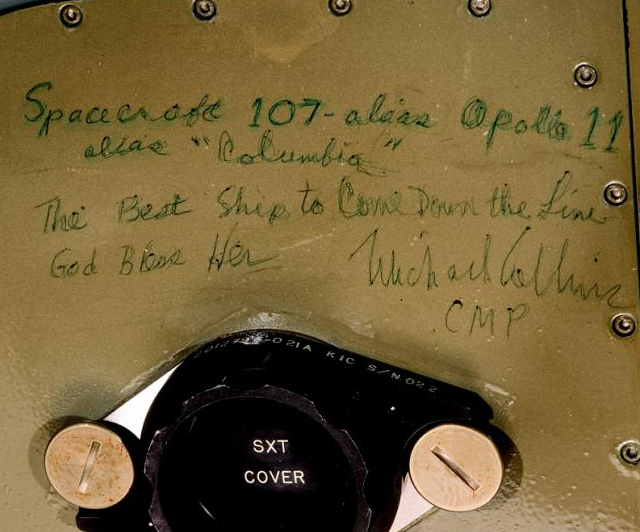

At the National Air and Space Museum, an interactive wall in the new Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall allows visitors to find objects, and more importantly, the stories surrounding them, to customize their tours, by combining the curatorial design of the exhibitions with their passions and interests.

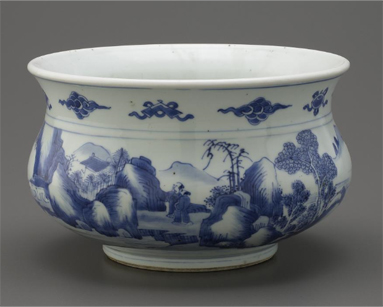

At the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery, in a room designed in the 19th century to house William Corcoran’s prized sculpture Greek Slave by Hiram Powers, stands a replica.

The sculpture is not a copy by Powers, which he did frequently, using the technology of his time, but rather a full-scale, polymer printout made using 3D data captured by the Smithsonian. And that data is available freely online for all who want to print their own.

This adaptation of our digital information will continue as our audiences grow and technology changes. The pace will quicken, too, beyond that first, life-changing but gradual evolution that commenced two decades ago.

And, if we move fast enough, opening all our collections and sharing all our work, our scientific investigations, political and cultural engagement and creativity will be available to and shared by everyone globally, reaching people where they are.

This idea is both audacious and thrilling.

I am exhilarated to be a part of the Smithsonian at such an incredible time, as we move out of our galleries and into the world to play a lead role in this ever-growing web of collaboration, producing unimagined new knowledge and experiences.

I hope you will join me.

Darren Milligan is the senior digital strategist, Smithsonian Center for Learning and Digital Access