Thought Leaders

This past year, our scholars stretched and challenged our thinking as they brought fresh perspectives to emerging cultural voices, the art of the Qur’an and species conservation.

Here's what four of them are saying.

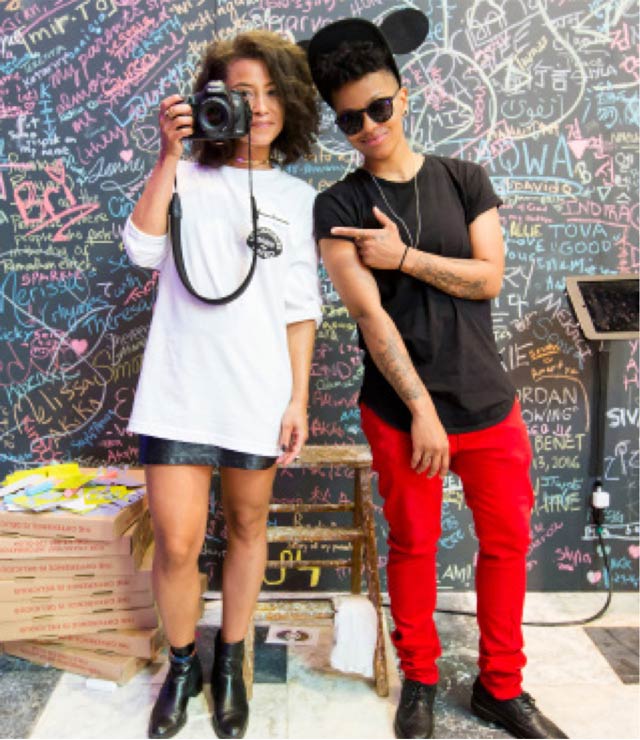

Adriel Luis

Adriel Luis explores the edges of cities, forgotten industrial zones and deep rural landscapes in search of artists creating new cultural identities in America. Partnering with communities to showcase these new voices, Luis’ democratic approach is upending how curators do their work and museums interact with the world around them.

“Most people make the assumption that museums tell you what to find important. I’m asking people in the community what they find important and how can I amplify that.

Storytelling has been transforming, especially with the emergence of online platforms. We are discovering stories assumed to be on the fringe, but that relate to people on a massive scale. We are starting to realize that the art and cultural canons aren’t necessarily the best indicators of human society, the pulse of humanity or society writ large. I grew up going to museums, but a lot of the ways I understood cultural dialogue and practices was going to swap meets, flea markets, block parties and cookouts.

At a culture lab, you won’t really find spaces where people are in complete silence, unless they are meditation spaces. Along with the labeled text and curated pieces, we do our best to have ambient noise in the form of music and kids playing and people talking.

We very intentionally show the seams of everything, from the art to the ways we curate it. We want to make the process transparent, so that people who are coming, if they’re coming as onlookers, current practitioners or aspiring practitioners, can see the process of how we got from point A to Z.

All that is to say we are using the exhibition as a vehicle for community development and engagement. As a curator, I am curating from the perspective of a community organizer.

I set out in D.C. to find stories outside of the frame of how we normally think this city reflects the rest of the country. Doing the original culture lab at the Arts and Industries Building on Memorial Day weekend, we were able to investigate the American identity, which is what the Smithsonian is known for, but looking at it from a 2016 point of view. Where are we today with American identity, looking at race, gender, sexuality or class?”

With support from the Ford Foundation, Luis has developed pop-up exhibitions he calls “culture labs.” Launched in Washington, D.C., he has since taken them to New York City and Honolulu.

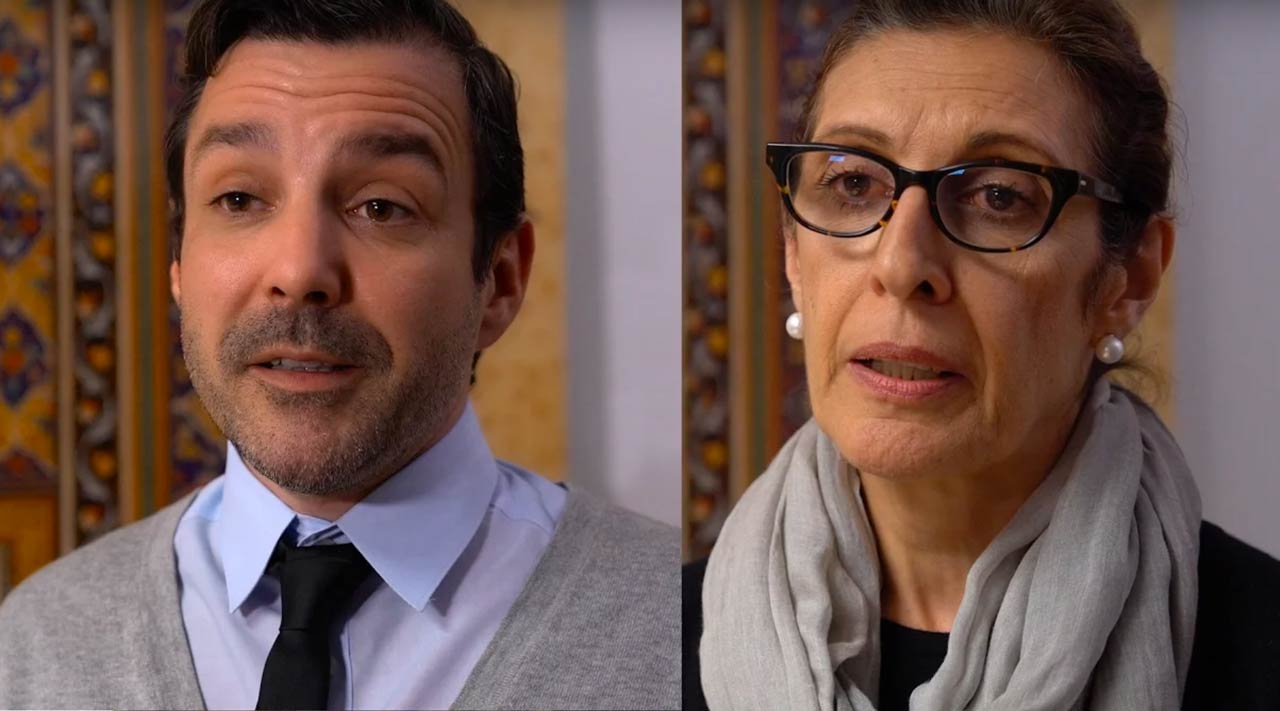

Massumeh Farhad and Simon Rettig

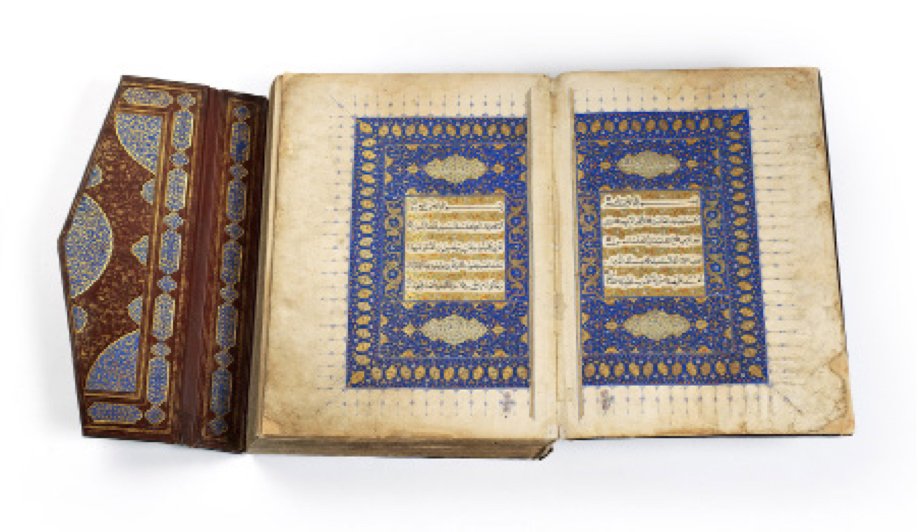

Massumeh Farhad and Simon Rettig curated The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, the first major exhibition on the Qur’an in the United States—against a backdrop of growing misconceptions about Islam’s holy book.

MF: If 10 years ago you told me I was going to do this exhibition, I’d say, ha, never. In a climate where anti-Islamic feeling is on the rise—and it’s been on the rise for some time—we had the full support of the Smithsonian. Remarkable.

SR: We realized that surprisingly little scholarship has been done on the holy book of Islam. We spent a month in Istanbul at the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, going through manuscripts page by page. These were texts collected from religious institutions, mosques and tombs, and we had the privilege of turning the pages, which made them come alive. We could get a sense of their historical context and the people who owned them. These manuscripts covered 1,000 years of production from an area that stretched from Egypt to Afghanistan. We were discovering how Qur’ans were made.

MF: Although the museum in Istanbul has a small staff, it holds one of the largest collections of Qur’an manuscripts in the world, including some of the oldest fragments. They were incredibly generous by lending 52 of their most precious examples. Once the exhibition opened, the impact was remarkable and we had a very large number of visitors, many of whom probably had never been to the Smithsonian before.

SR: We’ve received more than 3,500 notes. People flew from Atlanta, Detroit, California just to see the show.

MF: A rabbi came four times and brought his congregation. We saw all these people reading the labels, which is a real accomplishment, then actually talking to each other. We’ve had a comment card about a Muslim woman talking with a man from Israel. They were comparing notes. The Israeli said he didn’t know Abraham was in the Qur’an. He had come to Washington and found himself talking to a Muslim woman about something they had in common. This exhibition has started some dialogues and conversations, which are different from the conversations you hear in the media or anywhere else. I think that’s really important.

The exhibition traced development of the Qur’an over 1,000 years. Koç Holding was the principal sponsor.

Mel Songer

Mel Songer is part of an international team that returned 25 scimitar-horned oryx to their native grasslands in Chad in July. Extinct in the wild since the 1980s, the herd was fitted with GPS collars to track their movement and social behaviors, helping scientists build a self-sustaining population. Two calves have since been born to the herd.

People ask me, ‘Who really cares if we did lose the giant panda? So what?’ The so-called ‘charismatic megafauna’ I work on—giant pandas, Asian elephants, oryx, Przewalski’s horses—are umbrella species, meaning that if we maintain and restore them, we sustain their ecosystems and all their associated wildlife as well.

So, if we are protecting a large animal, which needs a large area to survive, we are protecting a large ecosystem, too. We are preserving biodiversity. In my view the underlying goal of conservation is to sustain ecosystems while ‘keeping all the pieces,’ as much as possible.

We cannot leave people out of the equation. Humans have been a part of nature for millions of years, and we are a part of natural systems. It’s not a realistic goal to just keep people out. We’ve got to understand how people are using these spaces. It’s a balancing act. When a species has gone extinct in the wild, there are a lot of factors that cause it—a change in the landscape, loss of habitat, and, in the case of the scimitar-horned oryx in Chad, the real kicker was pressure from the civil war.

The reserve where they were released in Chad is protected. It’s also the last place the oryx were in the wild. And, they’ve survived in zoos and large, enclosed ranches, which is why there’s a chance they can now go back to the wild and survive. We have to work with people to get their buy-in, so we don’t release 25 animals that are promptly shot. Strategically, we placed the oryx where there’s no well. They’re adapted and don’t need a lot of water. That isn’t true for livestock. So not a lot of livestock or people are coming through.

It takes a lot of money to return a species to the wild. This is a multimillion dollar operation. It’s probably the biggest project in terms of scale, number of animals released, having GPS collars on all of them and involving so many international organizations.

It’s an incredible opportunity to bring a range of science expertise together, partner with many stakeholders and develop conservation solutions that will make the place better for wildlife and people in a sustainable way.

Reintroducing the oryx required decades of work coordinated among the Environment Agency-Abu Dhabi, government of Chad government, Sahara Conservation Fund, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and the Zoological Society of London.