A Moment for the Nation

Director Lonnie Bunch, Rep. John Lewis, Michael Bonner and Shonda Rhimes reflect on the opening day of the National Museum of African American History and Culture

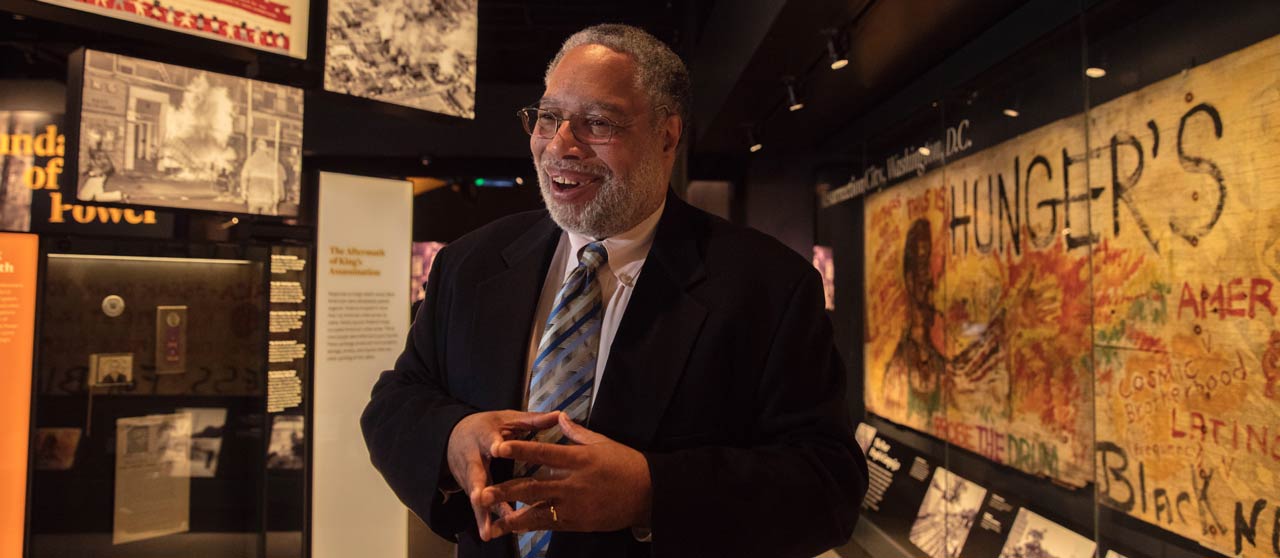

For the last 12 years, Lonnie Bunch made tens of thousands of decisions, large and small, as director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. He chose almost every quote for the museum’s walls, approved each story told in the exhibitions and oversaw, week by week, the construction of the 409,000-square-foot structure on the National Mall.

Yet, on the morning of Sept. 24 last year, the museum director hesitated. His tie. Which one fit the gravity of the day? Details mattered. A pale yellow and beige one to complement his gray suit, his daughters suggested.

Then, his speech. He was hours from making it, but he wanted it to capture the historic moment. He went back and forth over passages.

“There I was in the morning trying to figure out if my speech was too personal,” he said. “What did it mean in the broader sense? When I get nervous, I start rewriting. After all these years, the the dream was going to finally happen. It almost didn’t make any sense.”

But it did. This was the day the museum opened.

The occasion carried momentous significance, and all who were involved felt it that bright, clear September morning.

“The goal was to make our ancestors smile,” Bunch said. “For me, this day was the culmination of America at its best. The other thing I took away from that day, candidly, was okay, yeah, we did it. There were a lot of people who said we weren’t going get this done, didn’t believe in it, so there’s a part of me, the Jersey kid, who said, see.”

His tie knotted, his speech set, Bunch drew himself together. He was ready, just as the country was ready for the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The seeds for the day were planted in 2003, when Congress established the museum and allocated half of the $500 million needed for construction. The museum eventually raised $313 million, receiving gifts from more than 140,000 donors, including extraordinary leadership gifts from Oprah Winfrey, Robert Frederick Smith and Shonda Rhimes.

These donors—along with dignitaries and about 7,000 others—participated in the opening ceremony, receptions, dinners and a music festival. Millions more tuned in from their homes, workplaces, cars, cafes and airports.

The stage was constructed outside the museum, which had been designed to pay homage to the three-tiered Yoruba crowns from West Africa and the intricate ironwork crafted by enslaved African Americans in Louisiana, South Carolina and elsewhere. Bunch sat behind Presidents George Bush and Barack Obama and first ladies Laura Bush and Michelle Obama and beside Rep. John Lewis, “one of the few heroes I have,” he said.

Lewis stood first. To be on the podium, on that day, was a triumphant moment. A moment he had worked and hoped for nearly his entire career. As had so many before him. Most especially the African American veterans of the Union Army who first dreamed of a museum almost exactly a century before and his colleague Rep. Mickey Leland.

A permanent landmark in the nation’s capital. Before Lewis uttered a word, he scanned the audience.

“I looked out at this unbelievable crowd,” he said. “I looked straight ahead, then to the side. It reminded me of 1963 when I spoke at the March on Washington. It was almost unreal.”

In his speech, Lewis said, “we are gathered here today to dedicate a building, but this is more; it is a dream come true. As long as there is a United States of America, there will be a National Museum of African American History and Culture.”

His words carried across the crowd: “This museum is a testament to the dignity of the dispossessed in every corner of the globe who yearn for freedom. All the voices roaming, for centuries, have finally found a home here in this great monument to our pain, our suffering and our victory.”

His voice trembled. As he spoke, he remembered those who had not lived to see this day, the countless and nameless people who had given all they had during the centuries African Americans struggled in the United States.

“Long before I was born,” he said, “there were men and women who dreamed of the day that there would be an African American museum some place in Washington. They would have been very, very proud, pleased and happy to see this magnificent museum, located on the National Mall, what I call the front porch of America.”

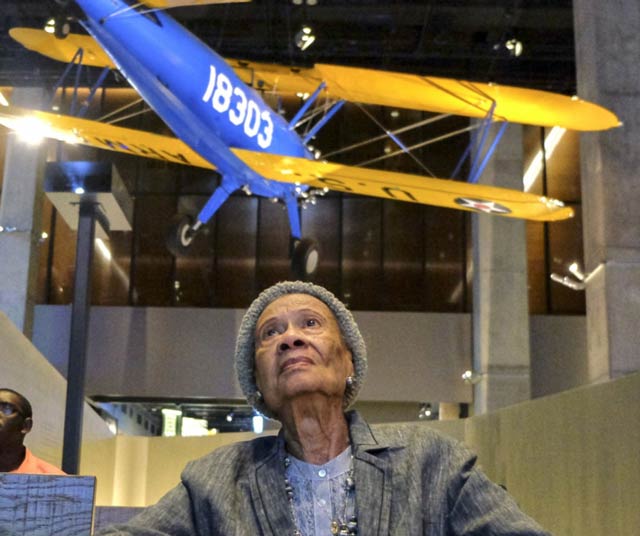

That day was seared in the minds and hearts of Michael Bonner and four generations of his family. He, his 99-year-old mother, 38-year-old son and 7-year-old granddaughter sat in a reception room before they would go on stage. Bonner’s mother, Ruth, was a special guest of honor. Her father, Elijah Odom, was born a slave in Mississippi, but escaped across a river to freedom. He studied and worked to own a general store and a pharmacy and was the only black physician in Biscoe, Ark.

At the end of the ceremony, Ruth Bonner joined the President and first lady in ringing the historic Freedom Bell to signify the opening of the museum, which recounts the epic journeys of African Americans—similar to her father—from Africa through slavery to American society today.

Michael Bonner, 75, detailed each minute of the day. “Everyone came over to meet my mother,” he reflected. “We met so many dignitaries, but the towering moment was ringing the bell. Quite unexpectedly, President Obama invited the remainder of my family to come onstage. It was a stark reminder that our ancestors were taken from Africa, endured the horrors of slavery and injustices of Jim Crow, yet they continued to rebound. We are grateful for all they achieved and committed to building on their legacies.”

“OUR ANCESTORS WERE TAKEN FROM AFRICA… YET THEY CONTINUED TO REBOUND. WE ARE GRATEFUL FOR ALL THEY ACHIEVED.”

MICHAEL BONNER

In the audience, Shonda Rhimes listened with her 14-year-old daughter, two sisters and parents as the bell was joined by the chiming of other bells across the city in a melodic call and response.

“It was joyous,” she said, “though slightly heartbreaking, sitting under the Washington Monument feeling we should have done this a long time ago. But, we were so proud. Everything was so emotional, John Lewis’ speech and President Obama’s.”

Late that night, after the opening and after the gala, Rhimes walked the museum with her family. They split into pairs on the first floor. “My daughter Harper and I walked at a certain pace,” she said. “My sisters walked at a certain pace and my parents walked at a certain pace. Harper slowed down and got more serious.”

She studied the artifacts, floor by floor. “The space is very moving,” Rhimes said. “When she came to Emmett Till’s casket, she didn’t feel she could see it. I understood and told her, ‘We can come back another time.’”

Now, the Hollywood producer and writer visits the museum whenever she is in Washington. The visual art gallery is named in her honor.

“We gave the gallery to the people of the United States for all time.”

Shonda Rhimes

“I told my daughter, ‘We gave the gallery to the people of the United States for all time,’” Rhimes said. “That impressed upon her the significance and meaning of charitable giving. You give what you have for what you believe.”

Months later on a winter afternoon, Bunch paused to reflect on how the opening day still reverberates through the country as he walked through the museum crowded with visitors. “I have great faith in an America that can overcome some political differences, can occasionally straddle the world of race and do something that makes us better because we do it together,” he said. “Maybe I am a tad optimistic and na´ve, but that is what I took away from that day.”

Ruth Odom Bonner passed away in August 2017, at age 100.